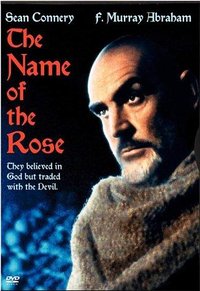

Der Name der Rose Quotes

An intellectually nonconformist monk investigates a series of mysterious deaths in an isolated abbey.

Adso of Melk: Master? Have you ever been in love?

William of Baskerville: In love? Yeah, many times.

Adso of Melk: You were?

William of Baskerville: Yes, of course. Aristotle, Ovid, Vergil...

Adso of Melk: No, no, no. I meant with a...

William of Baskerville: Oh. Ah. Are you not confusing love with lust?

Adso of Melk: Am I? I don't know. I want only her own good. I want her to be happy. I want to save her from her poverty.

William of Baskerville: Oh, dear.

Adso of Melk: Why "oh dear"?

William of Baskerville: You *are* in love.

Adso of Melk: Is that bad?

William of Baskerville: For a monk, it does present certain problems.

Adso of Melk: But doesn't St. Thomas Aquinas praise love above all other virtues?

William of Baskerville: Yes, the love of God, Adso. The love of God.

Adso of Melk: Oh... And the love of woman?

William of Baskerville: Of woman? Thomas Aquinas knew precious little, but the scriptures are very clear. Proverbs warns us, "Woman takes possession of a man's precious soul", while Ecclesiastes tells us, "More bitter than death is woman".

Adso of Melk: Yes, but what do you think, Master?

William of Baskerville: Well, of course I don't have the benefit of your experience, but I find it difficult to convince myself that God would have introduced such a foul being into creation without endowing her with *some* virtures. Hmm? How peaceful life would be without love, Adso, how safe, how tranquil, and how dull.

William of Baskerville: In love? Yeah, many times.

Adso of Melk: You were?

William of Baskerville: Yes, of course. Aristotle, Ovid, Vergil...

Adso of Melk: No, no, no. I meant with a...

William of Baskerville: Oh. Ah. Are you not confusing love with lust?

Adso of Melk: Am I? I don't know. I want only her own good. I want her to be happy. I want to save her from her poverty.

William of Baskerville: Oh, dear.

Adso of Melk: Why "oh dear"?

William of Baskerville: You *are* in love.

Adso of Melk: Is that bad?

William of Baskerville: For a monk, it does present certain problems.

Adso of Melk: But doesn't St. Thomas Aquinas praise love above all other virtues?

William of Baskerville: Yes, the love of God, Adso. The love of God.

Adso of Melk: Oh... And the love of woman?

William of Baskerville: Of woman? Thomas Aquinas knew precious little, but the scriptures are very clear. Proverbs warns us, "Woman takes possession of a man's precious soul", while Ecclesiastes tells us, "More bitter than death is woman".

Adso of Melk: Yes, but what do you think, Master?

William of Baskerville: Well, of course I don't have the benefit of your experience, but I find it difficult to convince myself that God would have introduced such a foul being into creation without endowing her with *some* virtures. Hmm? How peaceful life would be without love, Adso, how safe, how tranquil, and how dull.

William of Baskerville: My venerable brother, there are many books that speak of comedy. Why does this one fill you with such fear?

Jorge de Burgos: Because it's by Aristotle.

William of Baskerville: [Chasing after Jorge who runs with the Second Book of Poetics by Aristotle intending to destroy it] But what is so alarming about laughter?

Jorge de Burgos: Laughter kills fear, and without fear there can be no faith because without fear of the Devil, there is no more need of God.

William of Baskerville: But you will not eliminate laughter by eliminating that book.

Jorge de Burgos: No, to be sure, laughter will remain the common man's recreation. But what will happen if, because of this book, learned men were to pronounce it admissable to laugh at everything? Can we laugh at God? The world would relapse into chaos! Therefore, I seal that which was not to be said.

[he eats the poisoned pages of the book]

Jorge de Burgos: In the tomb I become.

[he tosses the book at the candle, which ignites a fire that destroys all the books in the abbey tower]

Jorge de Burgos: Because it's by Aristotle.

William of Baskerville: [Chasing after Jorge who runs with the Second Book of Poetics by Aristotle intending to destroy it] But what is so alarming about laughter?

Jorge de Burgos: Laughter kills fear, and without fear there can be no faith because without fear of the Devil, there is no more need of God.

William of Baskerville: But you will not eliminate laughter by eliminating that book.

Jorge de Burgos: No, to be sure, laughter will remain the common man's recreation. But what will happen if, because of this book, learned men were to pronounce it admissable to laugh at everything? Can we laugh at God? The world would relapse into chaos! Therefore, I seal that which was not to be said.

[he eats the poisoned pages of the book]

Jorge de Burgos: In the tomb I become.

[he tosses the book at the candle, which ignites a fire that destroys all the books in the abbey tower]

[last lines]

Voice of Adso as an Old Man: I have never regretted my decision, for I learned from my master much that was wise and good and true. When at last we parted company, he presented me with his eyeglasses. I was still young - he said - but someday they would serve me well. And in fact, I'm wearing them now on my nose as I write these lines. Then he embraced me fondly - like a father - and sent me on my way. I never saw him again, and know not what became of him, but I pray always that God received his soul, and forgave the many little vanities to which he was driven by his intellectual pride. And yet, now that I am an old, old man, I must confess that of all the faces that appear to me out of the past, the one I see most clearly is that of the girl of whom I've never ceased to dream these many long years. She was the only earthly love in my life, yet

[pause]

Voice of Adso as an Old Man: I never knew, nor ever learned, her name.

Voice of Adso as an Old Man: I have never regretted my decision, for I learned from my master much that was wise and good and true. When at last we parted company, he presented me with his eyeglasses. I was still young - he said - but someday they would serve me well. And in fact, I'm wearing them now on my nose as I write these lines. Then he embraced me fondly - like a father - and sent me on my way. I never saw him again, and know not what became of him, but I pray always that God received his soul, and forgave the many little vanities to which he was driven by his intellectual pride. And yet, now that I am an old, old man, I must confess that of all the faces that appear to me out of the past, the one I see most clearly is that of the girl of whom I've never ceased to dream these many long years. She was the only earthly love in my life, yet

[pause]

Voice of Adso as an Old Man: I never knew, nor ever learned, her name.

William of Baskerville: [after finding the secret room of books in the tower] How many more rooms? Ah! How many more books? No one should be forbidden to consult these books freely.

Adso of Melk: Perhaps they are thought to be too precious, too fragile.

William of Baskerville: No, it's not that, Adso. It's because they often contain a wisdom that is different from ours and ideas that could encourage us to doubt the infallability of the word of God... And doubt, Adso, is the enemy of faith.

Adso of Melk: Perhaps they are thought to be too precious, too fragile.

William of Baskerville: No, it's not that, Adso. It's because they often contain a wisdom that is different from ours and ideas that could encourage us to doubt the infallability of the word of God... And doubt, Adso, is the enemy of faith.

Jorge de Burgos: Laughter is a devilish wind which deforms, uh, the lineaments of the face and makes men look like monkeys.

William of Baskerville: Monkeys do not laugh. Laughter is particular to men.

Jorge de Burgos: As is sin. Christ never laughed.

William of Baskerville: Can we be so sure?

Jorge de Burgos: There is nothing in the Scriptures to say that he did.

William of Baskerville: And there's nothing in the Scriptures to say that he did not. Why, even the saints have been known to employ comedy, to ridicule the enemies of the Faith. For example, when the pagans plunged St. Maurice into the boiling water, he complained that his bath was too cold. The Sultan put his hand in... scalded himself.

William of Baskerville: Monkeys do not laugh. Laughter is particular to men.

Jorge de Burgos: As is sin. Christ never laughed.

William of Baskerville: Can we be so sure?

Jorge de Burgos: There is nothing in the Scriptures to say that he did.

William of Baskerville: And there's nothing in the Scriptures to say that he did not. Why, even the saints have been known to employ comedy, to ridicule the enemies of the Faith. For example, when the pagans plunged St. Maurice into the boiling water, he complained that his bath was too cold. The Sultan put his hand in... scalded himself.

Adso of Melk: And what was the word you both kept mentioning?

William of Baskerville: Penitenziagite.

Adso of Melk: What does it mean?

William of Baskerville: It means that the hunchback undoubtedly was once a heretic. Penitenziagite was a rallying cry of the dolcinites.

Adso of Melk: Dolcinites? Who were they, master?

William of Baskerville: Those who believed in the poverty of Christ.

Adso of Melk: So do we Franciscans.

William of Baskerville: But they also declared that everyone must be poor, so they slaughtered the rich. Ha! You see, Adso, the step between ecstatic vision and sinful frenzy is all too brief.

Adso of Melk: [looking at the Hunchback] Well, then, could he not have killed the translator?

William of Baskerville: No. No, fat bishops and wealthy priests were more to the taste of the dolcinites, hardly a specialist of Aristotle.

William of Baskerville: Penitenziagite.

Adso of Melk: What does it mean?

William of Baskerville: It means that the hunchback undoubtedly was once a heretic. Penitenziagite was a rallying cry of the dolcinites.

Adso of Melk: Dolcinites? Who were they, master?

William of Baskerville: Those who believed in the poverty of Christ.

Adso of Melk: So do we Franciscans.

William of Baskerville: But they also declared that everyone must be poor, so they slaughtered the rich. Ha! You see, Adso, the step between ecstatic vision and sinful frenzy is all too brief.

Adso of Melk: [looking at the Hunchback] Well, then, could he not have killed the translator?

William of Baskerville: No. No, fat bishops and wealthy priests were more to the taste of the dolcinites, hardly a specialist of Aristotle.

William of Baskerville: I too was an Inquisitor, but in the early days, when the Inquisition strove to guide, not to punish. And once I had to preside at a trial of a man whose only crime was to have translated a Greek book that conflicted with the Holy Scriptures. Bernardo Gui wanted him condemned as a heretic; I - acquitted the man. Then Bernardo Gui accused *me* of heresy, for having defended him. I appealed to the Pope. I - I was put in prison, tortured, and... and I recanted.

Adso of Melk: What happened then?

William of Baskerville: The man was burned at the stake and I am still alive.

Adso of Melk: What happened then?

William of Baskerville: The man was burned at the stake and I am still alive.

[first lines]

Voice of Adso as an Old Man: Having reached the end of my poor sinner's life, my hair now white, I prepare to leave on this parchment my testimony as to the wondrous and terrible events that I witnessed in my youth, towards the end of the year of our Lord 1327. May God grant me the wisdom and grace to be the faithful chronicler of the happenings that took place in a remote abbey in the dark north of Italy. An abbey whose name it seems, even now, pious and prudent to omit.

Voice of Adso as an Old Man: Having reached the end of my poor sinner's life, my hair now white, I prepare to leave on this parchment my testimony as to the wondrous and terrible events that I witnessed in my youth, towards the end of the year of our Lord 1327. May God grant me the wisdom and grace to be the faithful chronicler of the happenings that took place in a remote abbey in the dark north of Italy. An abbey whose name it seems, even now, pious and prudent to omit.

[Ubertino is talking man-to-man with Adso, showing him a statue of the Virgin Mary]

Ubertino da Casale: She's beautiful, is she not? When the female, by nature so perverse, becomes sublime by holiness, then she can be the noblest vehicle of grace.

[in Latin]

Ubertino da Casale: Beautiful are the breasts that protrude just a little.

Ubertino da Casale: She's beautiful, is she not? When the female, by nature so perverse, becomes sublime by holiness, then she can be the noblest vehicle of grace.

[in Latin]

Ubertino da Casale: Beautiful are the breasts that protrude just a little.

The Abbot: We found the body after a hailstorm, horribly mutilated, dashed against a rock at the foot of the tower, under a window which was, uh, how shall I say this? I trust...

William of Baskerville: Which was found closed.

The Abbot: Somebody told you?

William of Baskerville: Had it been found open, you would not have spoken of spiritual unease - you would have concluded that he'd fallen.

The Abbot: Brother William, the window cannot be opened! Nor was the glass shattered, nor is there any access to the roof above.

William of Baskerville: Which was found closed.

The Abbot: Somebody told you?

William of Baskerville: Had it been found open, you would not have spoken of spiritual unease - you would have concluded that he'd fallen.

The Abbot: Brother William, the window cannot be opened! Nor was the glass shattered, nor is there any access to the roof above.